Glaucoma treatment

Glaucoma refers to a group of eye conditions that lead to damage to the optic nerve head with progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells and their axons. This leads to a progressive loss of visual field. There are typical optic nerve changes on slit-lamp examination. Glaucoma is usually associated with an intraocular pressure (IOP) above the normal range. However:

20-52% (this varies between populations) of patients with glaucoma have IOP within the normal range. Patients with normal IOP who develop the characteristic changes associated with open-angle glaucoma are said to have low tension or normal pressure glaucoma.

Many patients have raised IOP for years without developing the changes of glaucoma. This condition is referred to as ocular hypertension.

Prior to 1978, glaucoma was defined as IOP above 21 mm Hg in an eye (the normal range is considered to be 10-21 mm Hg with 14 being the average). More recently glaucoma has been understood as an abnormal physiology in the optic nerve head that interacts with the IOP, with the degree and rate of damage relating to both factors.

TYPES OF GLAUCOMA

There are several glaucoma subtypes, although all are considered optic neuropathies.

Glaucoma may be primary or secondary to other conditions.

Glaucoma may be open-angle or closed-angle.

Glaucoma may be acute, acute-on-chronic, intermittent or chronic.

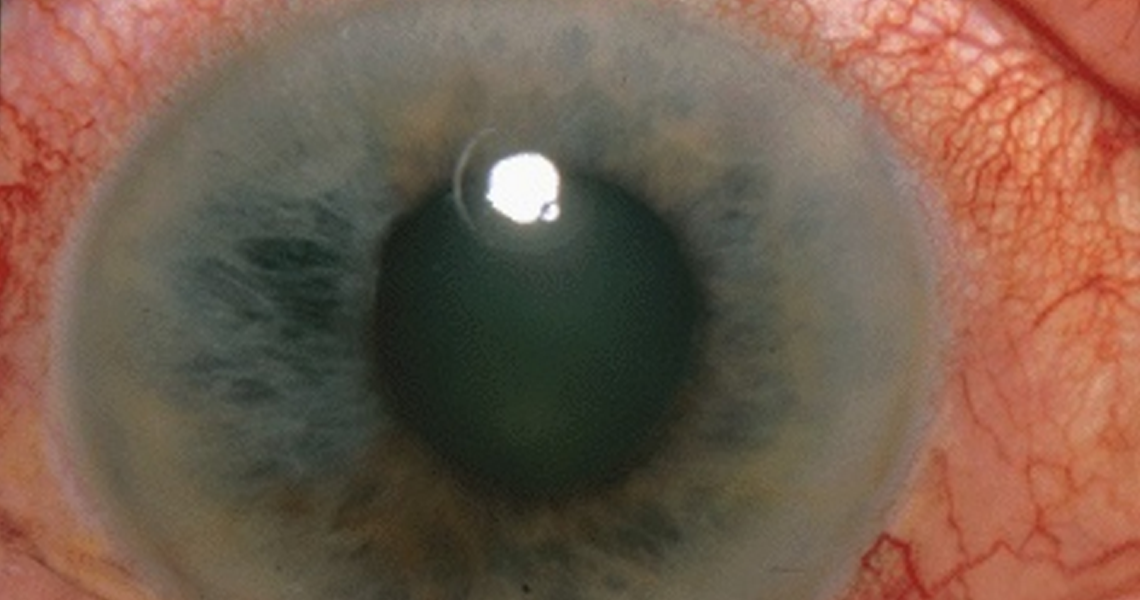

The end stage of glaucoma is referred to as absolute glaucoma. There is no functioning vision, the pupillary reflex is lost and the eye has a stony appearance. The condition is very painful .

Other separate articles that you may find relevant are Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension, Angle-closure Glaucoma and Congenital Primary Glaucoma.

SIMPLE (PRIMARY) OPEN-ANGLE GLAUCOMA

Simple (primary) open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is a progressive, chronic condition characterised by:

Adult onset.

IOP at some point greater than 21 mm Hg (normal range: about 10-21 mm Hg).

An open iridocorneal angle (between the iris and the cornea, where the aqueous flows out).

Glaucomatous optic neuropathy.

Visual field loss compatible with nerve fibre damage.

Absence of an underlying cause.

It is usually bilateral.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The primary problem in glaucoma is disease of the optic nerve. The pathophysiology is not fully understood but there is a progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells and their axons. In its early stages it affects peripheral visual field only but as it advances it affects central vision and results in loss of visual acuity, which can lead to severe sight impairment and complete loss of vision.

For most types of glaucoma, optic neuropathy is associated with a raised IOP. This has given rise to the hypothesis of retinal ganglion apoptosis, whose rate is influenced by the hydrostatic pressure on the optic nerve head and by compromise of the local microvasculature. The resulting optic neuropathy gives rise to the characteristic optic disc changes and visual field loss.

In open-angle glaucoma, flow is reduced through the trabecular meshwork (whose role is absorbing aqueous humour). This is a chronic degenerative obstruction which occurs painlessly.

The IOP is not always raised: in normal-tension glaucoma (NTG), IOP is in the normal range, which has led to other theories, including vascular perfusion problems or an autoimmune component. Others have postulated that the optic nerve head is particularly sensitive in these patients, with damage occurring at much lower IOPs than in normal individuals. This could explain why these patients benefit from IOP-lowering medication.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

This is the most common form of glaucoma.

Approximately 1-2% of the population aged over 40 are affected but about half are unaware of this.

Prevalence increases with age, affecting about 10% of people aged over 70.

RISK FACTORS

Age- the incidence increases with age, most commonly presenting after the age of 65 (and rarely before the age of 40).

Family history- there is a clear inherited component in many individuals (IOP, aqueous outflow facilities and disc size are inherited characteristics). However, it is thought that there is incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity of the genes involved. There are also several factors thought to contribute to the inheritance and therefore the risk to relatives is currently only an estimate: 4% to children and 10% to siblings of an affected individual.

Race- it is three to four times more common in Afro-Caribbean people in whom it tends to present earlier and is more severe.

Ocular hypertension- this is a major risk factor for the development of glaucoma with about 9% of patients developing glaucoma over five years if left untreated.

Other factors- myopia (short-sightedness) and retinal disease (eg, central retinal vein occlusion, retinal detachment and retinitis pigmentosa) can predispose individuals to POAG. Diabetes and systemic hypertension (and possibly also systolic hypotension may also contribute to risk.

PRESENTATION

Unfortunately, in the vast majority of cases, patients are asymptomatic. Because initial visual loss is to peripheral vision and the field of vision is covered by the other eye, patients do not notice visual loss until severe and permanent damage has occurred, often impacting on central (foveal) vision. By then, up to 90% of the optic nerve fibres may have been irreversibly damaged.

Open-angle glaucoma may be detected on checking the IOPs and visual fields of those with affected relatives. Suspicion may arise during the course of a routine eye check by an optician or GP, where abnormal discs, IOPs or visual fields may be noted.

EXAMINATION

An ophthalmologist will examine the eye thoroughly for evidence of glaucoma, comorbidity or an alternative diagnosis to the apparent findings. The details of a glaucoma assessment can be summarised as:

Gonioscopy- a technique used to measure the angle between the cornea and the iris to assess whether the glaucoma is open-angle or closed-angle.

Corneal thickness- this influences the IOP reading. If it is thicker than usual, it will take greater force to indent the cornea and an erroneously high reading will be obtained.

Tonometry- this is the objective measurement of IOP, usually based on the assessment of resistance of the cornea to indent. The normal range is considered to be 10 mm Hg-21 mm Hg.

Optic disc examination- this is a direct marker of disease progression. Optic disc damage is assessed by looking at the cup:disc ratio: normal is 0.3, although it can be up to 0.7 in some normal people:

Glaucoma is suggested by an increase in cupping with time, rather than by cupping alone. Marked but stable cupping may be hereditary.

The intra-observer variability in optic disc evaluation has been reduced by use of ocular coherence tomography (OCT), which produces excellent visual records and provides quantification of exact cup:disc ratio and areas of neuroretinal thinning.

Visual fields- assessment requires the co-operation of the patient and can also be affected by fatigue, spectacle frames, miosis and media opacities. See also the separate Visual Field Defects

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance (2009) states that at diagnosis all people with chronic open-angle glaucoma (COAG), suspected COAG or ocular hypertension (OHT) should have:

Goldmann tonometry for IOP measurement.

Corneal thickness measurement.

Gonioscopy (anterior chamber configuration and depth).

Perimetry (visual field measurements).

Slit-lamp assessment of the optic nerve and fundus (pupil dilated).

NICE also states that at each visit the following should be available:

Records of all previous tests.

Records of past medical history.

Current medication list (systemic and topical).

Glaucoma medication record.

Allergies and intolerances.

GRADING OF SIMPLE (PRIMARY) OPEN-ANGLE GLAUCOMA

Mild- early visual field defects.

Moderate- presence of an arcuate scotoma ('n'-shaped visual field loss arching over the central visual field) and thinning of neuroretinal rim (cupping).

Severe- extensive visual field loss and marked thinning of the neuroretinal rim.

End-stage- only a small residual visual field remains. There may be very little neuroretinal rim remaining (cup:disc ratio would be in the region of 0.9-1.0).

MANAGEMENT

There are variations across the NHS in management of this condition, reflecting conflicting literature and scattered reports. NICE guidelines (2009) and SIGN (2015) guidance attempt to offer clear recommendations on testing, diagnosis, monitoring and treatment.

Treatment aims

Treatment is not necessarily started immediately on simple detection of an elevated IOP. Given the potential for variation of findings from one assessment to the next, the patient should be assessed on several occasions unless the findings are unequivocal - the diagnosis is significant and treatment is usually lifelong. Apparent disc cupping is considered in conjunction with visual fields and IOP. In some patients, the disease is obvious and advanced, in which case treatment should start promptly.

Once a diagnosis and decision to treat have been made, a target IOP is set according to the degree of damage: this is the pressure below which further damage is considered unlikely. This is usually in the region of a 30% drop of IOP. It differs between patients and may be different in each eye.

Regular monitoring to assess IOP, the optic disc and the visual fields. Some areas have schemes whereby trained opticians carry out all the monitoring.

Patient education is essential, as this is a largely asymptomatic condition until it is very advanced and medication compliance is often poor.Patients need to understand the irreversible nature of the disease, how to take drops correctly and their potential side-effects. They also need to be advised of the risk to other family members.

DRIVING AND GLAUCOMA

A visual field defect counts as a 'relevant disability' (as opposed to the 'absolute disability' of a reduced visual acuity) in law. There are certain criteria set out and assessed by the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency.

PROGNOSIS

Unless treated, COAG is progressive. Treatment aims to stall this progression but cannot reverse it. However, if treatment is timely, appropriate and maintained, useful vision can be expected to be maintained throughout the patient's lifetime.

Factors involved in more rapid progression include myopia, the presence of optic disc haemorrhages, vascular factors and genetic factors. Although there is not an associated mortality per se, studies have shown cardiovascular mortality tending to increase in people of African ethnicity with previously diagnosed/treated POAG and ocular hypertension.

PREVENTION

POAG cannot be prevented but its progression can be slowed if it is detected and treated. By and large, the patient will not notice symptoms relating to POAG until the visual field changes are very advanced, at which point very little can be done. For this reason, screening remains the only tool for detection, with shared care between optometrists and ophthalmologists underpinning the detection and management. It should involve tonometry (measuring the IOP), visual fields and an examination of the optic disc.

Where there is no family history, opportunistic screening can be performed (ideally every two years) when the patient goes for a routine visit to their optician. From the age of 65 this should be carried out yearly.

In patients with a first-degree relative with POAG, a full specialist optician or ophthalmologist review should be carried out at the age of 40, with further screening every two years until the age of 50, and yearly thereafter. Shorter inter-screening intervals are recommended for patients with raised IOPs and patients considered otherwise at risk of POAG.